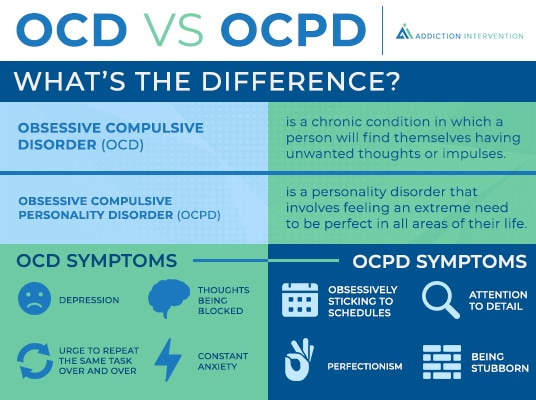

Despite having similar names, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) are two distinct mental health diseases that present differently in each individual. Both can have a significant influence on day-to-day living, but correctly diagnosing and treating each requires a grasp of their differences.

Obsessions, or unwanted, intrusive thoughts, and compulsions, or repetitive actions or thoughts, are characteristics of OCD. These compulsions develop in an effort to lessen the anxiety brought on by the obsessions or to prevent a circumstance or occurrence that is feared. For example, someone may have a recurring fear that their home would burn down, which makes them constantly check to make sure the stove is off. Even if these actions appear unreasonable to others, OCD sufferers find some solace in them.

Conversely, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCPD) is typified by a persistent obsession with control, order, and regulations. The behaviors associated with OCPD are caused by an ingrained idea that their method is the "best" or "right" way to accomplish things, in contrast to the compulsions associated with OCD, which are motivated by intrusive thoughts or worries. Perfectionists who frequently hold others and themselves to impossible standards are individuals with OCPD. This may result in an obsession with to-do lists, calendars, and organizing, often to the expense of social interactions or recreational pursuits.

From a neuroscientific perspective, the genesis of these conditions is intricate and varied. Studies on OCD indicate that anomalies in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and basal ganglia may contribute to the disorder. These regions are important in processing fear, controlling behavior, and making decisions. Serotonin and other neurotransmitter imbalances are thought to play a role as well. The exact neurological causes of OCPD are unknown, however a mix of brain-based, environmental, and hereditary variables are thought to be involved.

The complexities of OCD have been illuminated by a number of well-known cases of persons with the disorder throughout history. One such instance is the life of wealthy filmmaker and aviator Howard Hughes, whose severe OCD had a significant impact on his quality of life. His excessive isolation and habits, such as storing his pee in jars, were caused by his dread of germs. Despite the severity of Hughes's situation, it highlights how crippling untreated OCD can be.

These illnesses vary in frequency. Both adults and children are affected by OCD, which is ranked as one of the top 20 causes of illness-related disability by the World Health Organization. On the other hand, with an estimated 8% of the population affected, OCPD is thought to be the most common personality disorder.

Assessing for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) requires a combination of clinical interviews, standardized assessment tools, and sometimes observational methods. Here are some commonly used tests and assessment tools for both disorders:

For OCD:

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS): This is the most widely used instrument to assess the severity of OCD symptoms. It evaluates the time occupied by obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, the associated distress, resistance against the obsessions or compulsions, and the degree of control over them.

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (OCI): A self-report scale that measures the severity of various OCD symptoms. It's shorter than the Y-BOCS and can be useful for tracking symptom changes over time.

Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS): Specifically designed for children and adolescents, this tool assesses the type and severity of OCD symptoms in younger populations.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID): While it covers a range of disorders, it has specific sections dedicated to assessing OCD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria.

For OCPD:

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4): A self-report questionnaire designed to assess a range of personality disorders, including OCPD.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2): While it's a broad measure of personality and psychopathology, it has scales that can help in identifying features consistent with OCPD.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID-II): This is the personality disorders version of the SCID and includes a section specifically for OCPD.

Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-III): This is another comprehensive psychological assessment tool that evaluates long-standing personality patterns, including those of OCPD.

Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI): A more recent instrument that assesses personality disorders, including OCPD, through self-report.

In addition to these standardized tests, a thorough clinical interview by a trained mental health professional is essential. The professional will often ask about the individual's history, the onset of symptoms, their duration and severity, and the impact of these symptoms on daily functioning. Observations of behavior, collateral information from family or close friends, and a review of previous medical or psychiatric records can also provide valuable insights.

Each illness requires a different strategy to treatment. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and cognitive-behavioral therapy, particularly Exposure and Response Prevention, are effective treatments for OCD. Because of its deep-rooted status as a personality disorder, OCPD can be more difficult to cure. Therapy, however, can provide people with techniques to identify and deal with their obsessive habits and inflexible thought patterns.

In conclusion, despite some surface-level parallels, OCD and OCPD are two different illnesses with different symptoms, etiologies, and therapeutic approaches. Understanding these distinctions is essential for individuals impacted and the professionals who assist them, and it goes beyond simple academic research. A mental health expert can help you or someone you know who is exhibiting symptoms of either disease so that you can have a better knowledge and a higher quality of life.